Olmsted Linear Park in Atlanta

|

Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.

Frederick Law Olmsted was born in Hartford, Connecticut, a member of the eighth generation of his family to live in that city. His mother died when he was four, and from the age of seven he received his schooling mostly from ministers in outlying towns, with whom he lived. His father, a successful dry-goods merchant, was a lover of scenery, and much of Olmsted's vacation time was spent with his family on "tours in search of the picturesque" through northern New England and upstate New York. As he was about to enter Yale College in 1837, Olmsted suffered severe sumac poisoning, which weakened his eyes and kept him from the usual course of studies.

He spent the next twenty years gathering experiences and skills from a variety of endeavors that he eventually utilized in creating the profession of landscape architecture. He worked in a New York dry-goods store and took a year-long voyage in the China Trade. He studied surveying and engineering, chemistry, and scientific farming, and ran a farm on Staten Island from 1848 to 1855. In 1850 he and two friends took a six-month walking tour of Europe and the British Isles, during which he saw numerous parks and private estates, as well as scenic countryside. In 1852 he published his first book, Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England. That December he began the first of two journeys through the slave-holding south as a reporter for the New York Times. Between 1856 and 1860 he published three volumes of travel accounts and social analysis of the South. During this period he used his literary activities to oppose the westward expansion of slavery and to argue for the abolition of slavery by the southern states. From 1855 to 1857 he was partner in a publishing firm and managing editor of Putnam's Monthly Magazine, a leading journal of literature and political commentary. He spent six months of this time living in London with considerable travel on the Continent, and in the process visited many public parks.

He spent the next twenty years gathering experiences and skills from a variety of endeavors that he eventually utilized in creating the profession of landscape architecture. He worked in a New York dry-goods store and took a year-long voyage in the China Trade. He studied surveying and engineering, chemistry, and scientific farming, and ran a farm on Staten Island from 1848 to 1855. In 1850 he and two friends took a six-month walking tour of Europe and the British Isles, during which he saw numerous parks and private estates, as well as scenic countryside. In 1852 he published his first book, Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England. That December he began the first of two journeys through the slave-holding south as a reporter for the New York Times. Between 1856 and 1860 he published three volumes of travel accounts and social analysis of the South. During this period he used his literary activities to oppose the westward expansion of slavery and to argue for the abolition of slavery by the southern states. From 1855 to 1857 he was partner in a publishing firm and managing editor of Putnam's Monthly Magazine, a leading journal of literature and political commentary. He spent six months of this time living in London with considerable travel on the Continent, and in the process visited many public parks.

OLMSTED'S LATER WORK

In the fall of 1857, Olmsted's literary connections enabled him to secure the position of superintendent of Central Park in New York City. The following March, he and Calvert Vaux won the design competition for the park. During the next seven years he was primarily an administrator in charge of major undertakings: first (1859-1861) as architect-in-chief of Central Park, in charge of construction of the park; then (1861–1863) as director of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, charged with overseeing the health and camp sanitation of all the volunteer soldiers of the Union Army and with creating a national system of medical supply for those troops; and finally (1863-1865) as manager of the Mariposa Estate, a vast gold-mining complex in California.

In 1865, Olmsted returned to New York to join Vaux in completing their work on Central Park and designing Prospect Park in Brooklyn. Over the next thirty years, ending with his retirement in 1895, Olmsted created examples of the many kinds of designs by which the profession of landscape architecture (a term he and Vaux first used) could improve the quality of life in America. These included the large urban park, devoted primarily to the experience of scenery and designed so as to counteract the artificiality of the city and the stress of urban life; the "parkway," a wide urban greenway carrying several different modes of transportation (most important a smooth-surfaced drive reserved for private carriages) which connected parks and extended the benefits of public greenspace throughout the city; the park system, offering a wide range of public recreation facilities for all residents in a city; the scenic reservation, protecting areas of special scenic beauty from destruction and commercial exploitation; the residential suburb, separating place of work from place of residence and devoted to creating a sense of community and a setting for domestic life; the grounds of the private residence, where gardening could develop both the aesthetic awareness and the individuality of its occupants, and containing numerous "attractive open-air apartments" that permitted household activities to be moved outdoors; the campuses of residential institutions, where a domestic scale for the buildings would provide a training ground for civilized life; and the grounds of government buildings, where the function of the buildings would be made more efficient and their dignity of appearance increase by careful planning. In each of these categories, Olmsted developed a distinctive design approach that showed the comprehensiveness of his vision, his uniqueness of conception that he brought to each commission, and the imagination with which he dealt with even the smallest details.

PRINCIPAL PROJECTS

His principal projects in each category are:

Scenic Reservations

Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove (1865) and Niagara Reservation (1887).

Major Urban Parks

Central Park (1858); Prospect Park (1866); Delaware Park, Buffalo (1869); South Park (later Washington and Jackson Parks and Midway Plaisance), Chicago (1871); Belle Isle, Detroit (1881); Mount Royal, Montreal (1877); Franklin Park, Boston (1885); Genesee Valley Park, Rochester, New York (1890); Cherokee Park, Louisville (1891). Also notable were Riverside Park (1875) and Morningside Park (1873 and 1887) in New York and Fort Greene Park (1868) in Brooklyn. In smaller cities, Walnut Hill Park in New Britain, Connecticut (1870); South (now Kennedy) Park in Fall River, Massachusetts (1871); Beardsley Park in Bridgeport, Connecticut (1884); Downing Park in Newburgh, New York (1887), and Cadwalader Park, Trenton, New Jersey (1891).

Parkways

Eastern and Ocean parkways, Brooklyn (1868); Humboldt and Lincoln, Bidwell and Chapin Parkways, Buffalo (1870); Drexel Boulevard and Martin Luther King Drive, Chicago (1871); the "Emerald Necklace" (1881 on), Beacon Street, and Commonwealth Avenue extension (1886) in Boston; and Southern Parkway, Louisville (1892).

Park Systems

Buffalo-Delaware Park, The Front, The Parade, South Park and Cazenovia Park, and connecting parkways. Boston-the "Emerald Necklace": Charlesbank, Back Bay Fens, Riverway, Leverett Park, Jamaica Pond, Arnold Arboretum, Franklin Park, and Marine Park, and connecting parkways. Rochester-Genesee Valley, Highland, and Seneca Parks and several city squares. Louisville-Shawnee, Cherokee, and Iroquois Parks, Southern Parkways and several small city parks and squares.

Residential Communities

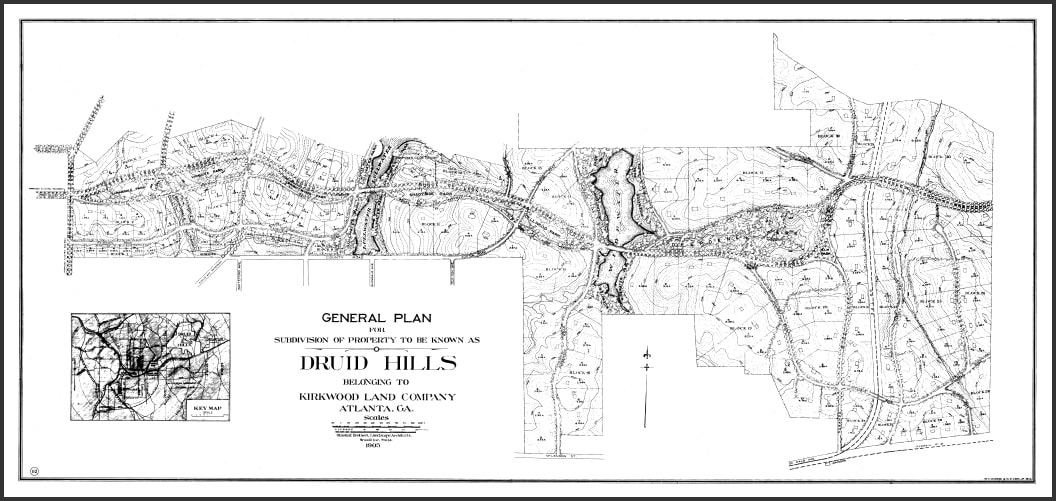

Riverside, Illinois (1869); Sudbrook, Maryland (1889); Druid Hills, Atlanta (1893).

Residential Campuses

Stanford University (1886); Lawrenceville School (1884); Buffalo State Hospital for the Insane (1875); Hartford Retreat (1860); Bloomingdale Asylum, White Plains, New York (1892).

Government Buildings

U.S. Capitol grounds and terraces (1874); Connecticut State House (1878).

Country Estates

Olmsted designed a number of large estates, and with some of these he introduced projects with public significance, particularly scientific forestry and arboretums. The outstanding examples are Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, and Moraine Farm in Beverly, Massachusetts.

SOURCE: National Association for Olmsted Parks

In the fall of 1857, Olmsted's literary connections enabled him to secure the position of superintendent of Central Park in New York City. The following March, he and Calvert Vaux won the design competition for the park. During the next seven years he was primarily an administrator in charge of major undertakings: first (1859-1861) as architect-in-chief of Central Park, in charge of construction of the park; then (1861–1863) as director of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, charged with overseeing the health and camp sanitation of all the volunteer soldiers of the Union Army and with creating a national system of medical supply for those troops; and finally (1863-1865) as manager of the Mariposa Estate, a vast gold-mining complex in California.

In 1865, Olmsted returned to New York to join Vaux in completing their work on Central Park and designing Prospect Park in Brooklyn. Over the next thirty years, ending with his retirement in 1895, Olmsted created examples of the many kinds of designs by which the profession of landscape architecture (a term he and Vaux first used) could improve the quality of life in America. These included the large urban park, devoted primarily to the experience of scenery and designed so as to counteract the artificiality of the city and the stress of urban life; the "parkway," a wide urban greenway carrying several different modes of transportation (most important a smooth-surfaced drive reserved for private carriages) which connected parks and extended the benefits of public greenspace throughout the city; the park system, offering a wide range of public recreation facilities for all residents in a city; the scenic reservation, protecting areas of special scenic beauty from destruction and commercial exploitation; the residential suburb, separating place of work from place of residence and devoted to creating a sense of community and a setting for domestic life; the grounds of the private residence, where gardening could develop both the aesthetic awareness and the individuality of its occupants, and containing numerous "attractive open-air apartments" that permitted household activities to be moved outdoors; the campuses of residential institutions, where a domestic scale for the buildings would provide a training ground for civilized life; and the grounds of government buildings, where the function of the buildings would be made more efficient and their dignity of appearance increase by careful planning. In each of these categories, Olmsted developed a distinctive design approach that showed the comprehensiveness of his vision, his uniqueness of conception that he brought to each commission, and the imagination with which he dealt with even the smallest details.

PRINCIPAL PROJECTS

His principal projects in each category are:

Scenic Reservations

Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove (1865) and Niagara Reservation (1887).

Major Urban Parks

Central Park (1858); Prospect Park (1866); Delaware Park, Buffalo (1869); South Park (later Washington and Jackson Parks and Midway Plaisance), Chicago (1871); Belle Isle, Detroit (1881); Mount Royal, Montreal (1877); Franklin Park, Boston (1885); Genesee Valley Park, Rochester, New York (1890); Cherokee Park, Louisville (1891). Also notable were Riverside Park (1875) and Morningside Park (1873 and 1887) in New York and Fort Greene Park (1868) in Brooklyn. In smaller cities, Walnut Hill Park in New Britain, Connecticut (1870); South (now Kennedy) Park in Fall River, Massachusetts (1871); Beardsley Park in Bridgeport, Connecticut (1884); Downing Park in Newburgh, New York (1887), and Cadwalader Park, Trenton, New Jersey (1891).

Parkways

Eastern and Ocean parkways, Brooklyn (1868); Humboldt and Lincoln, Bidwell and Chapin Parkways, Buffalo (1870); Drexel Boulevard and Martin Luther King Drive, Chicago (1871); the "Emerald Necklace" (1881 on), Beacon Street, and Commonwealth Avenue extension (1886) in Boston; and Southern Parkway, Louisville (1892).

Park Systems

Buffalo-Delaware Park, The Front, The Parade, South Park and Cazenovia Park, and connecting parkways. Boston-the "Emerald Necklace": Charlesbank, Back Bay Fens, Riverway, Leverett Park, Jamaica Pond, Arnold Arboretum, Franklin Park, and Marine Park, and connecting parkways. Rochester-Genesee Valley, Highland, and Seneca Parks and several city squares. Louisville-Shawnee, Cherokee, and Iroquois Parks, Southern Parkways and several small city parks and squares.

Residential Communities

Riverside, Illinois (1869); Sudbrook, Maryland (1889); Druid Hills, Atlanta (1893).

Residential Campuses

Stanford University (1886); Lawrenceville School (1884); Buffalo State Hospital for the Insane (1875); Hartford Retreat (1860); Bloomingdale Asylum, White Plains, New York (1892).

Government Buildings

U.S. Capitol grounds and terraces (1874); Connecticut State House (1878).

Country Estates

Olmsted designed a number of large estates, and with some of these he introduced projects with public significance, particularly scientific forestry and arboretums. The outstanding examples are Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, and Moraine Farm in Beverly, Massachusetts.

SOURCE: National Association for Olmsted Parks