Grant Park

|

The Grant Park neighborhood was built around Grant Park, a 131-acre green space and recreational area. One of Atlanta’s oldest residential neighborhoods, it occupies over 430 acres of rolling terrain southeast Atlanta. The majority of the structures in the Grant Park neighborhood are residential but the area also includes the school buildings, churches, neighborhood commercial clusters and recreational buildings that have served the historic neighborhood. Rambling Victorian era mansions and small cottages, early twentieth century bungalows and many brick paved sidewalks characterize the neighborhood.

|

|

A majority of the structures were built from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century. Large two-story mansions were constructed face the park, more modest two-story, modified Queen Anne, frame dwellings were constructed on surrounding streets, one-story Victorian era cottages and Craftsman bungalows predominate in the streets to the east of the park.

Grant Park’s distinctive landscape includes rolling hills and scenic vistas. The neighborhood’s grid street pattern and narrow rectangular lots which developed during the 1890s and early 1900s are representative of Atlanta residential plans of this era. The streets are lined with mature trees and there is an extensive sidewalk system, portions of which are the original brick. Due to the topography, retaining walls are an important landscape feature.

Throughout its existence, Grant Park has provided a respite for the city dweller as a place for recreation and amusement. The neighborhood’s retention of its street patterns, landscape architecture, and public amenities from its formative period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries contributes to the historic environment which makes Grant Park one of Atlanta’s most valuable and significant early residential districts.

Grant Park’s distinctive landscape includes rolling hills and scenic vistas. The neighborhood’s grid street pattern and narrow rectangular lots which developed during the 1890s and early 1900s are representative of Atlanta residential plans of this era. The streets are lined with mature trees and there is an extensive sidewalk system, portions of which are the original brick. Due to the topography, retaining walls are an important landscape feature.

Throughout its existence, Grant Park has provided a respite for the city dweller as a place for recreation and amusement. The neighborhood’s retention of its street patterns, landscape architecture, and public amenities from its formative period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries contributes to the historic environment which makes Grant Park one of Atlanta’s most valuable and significant early residential districts.

Cultural and Historical Significance

The Grant Park neighborhood developed around the park land that Lemuel P. Grant donated to the city on May 17, 1883. Grant had purchased large tracts of land southeast of the city in the 1840s and later subdivided the property and sold the lots for residential development.

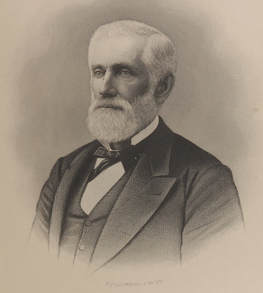

Lemuel Pratt Grant was born in Frankfurt, Maine in 1817. He began working for the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad working his way up quickly in the business. He was hired in 1840 to work as an assistant in the Georgia Railroad’s corps of engineers. From 1840 until well into the 1870s, Grant continued his involvement in railroad building, working for several lines including the Central Railroad of Georgia, the Atlanta and West Point Railroad and Georgia Western (now Georgia Pacific). Grant’s contributions to the expanding rail lines in and around Atlanta made him a prominent figure in the growth and expansion of the city as a transportation center. John Robert Smith, in his article on Grant as a railroadman, states, "more perhaps than any other person, Lemuel Grant sparked the development of the very rail system by which the City of Atlanta was launched into greatness" (Atlanta Historical Journal, Summer 1980).

Grant was made a colonel in the Confederate Army in 1862. During late 1863 and early 1864, Grant was responsible for the design and construction of a system of defensive fortifications for the City of Atlanta. A section of the main line of these earthen breastworks bbbisected some of Grant’s property that now lies within Grant Park and a southeast salient extended to the southeast corner of the park where Fort Walker is still in evidence.

After the war, Grant expanded his business career. He continued his railroad activity (becoming an officer of several lines), participated in early street railway building, developed his real estate interests and served local government in several capacities. In 1869 Grant became a member of Atlanta’s first Board of Education and was very active in the 1870s in establishing the public school system in Atlanta. At one time, Grant’s land holdings made him the largest landowner in southeast Atlanta.

As might be expected from its name, the neighborhood owes much of its development primarily to decisions made by Lemuel Pratt Grant, particularly his decisions first to buy large tracts of land southeast of the city in the 1840s and 1850s, second, to hold the tract through the 1870s, and finally to subdivide and sell them in the 1880s. A second formative force has persistently influenced the area’s development: the growth and resultant need for housing in Atlanta itself. This growth alternately circumscribed and spurred the Neighborhood’s growth through several eras, from the first streetcar lines up through the building of the superhighway. The interplay between the private decisions of Grant and landowners like him and the public need for residential sites around the blossoming downtown districts defines much of the development of the neighborhood.

Initially, the early neighborhood must have seemed a nearly rural domain on the fringes of bustling Atlanta. In the 1850s the city founded its main cemetery, Oakland, on the north side of Fair Street (Memorial Drive). Oakland Cemetery has ever since defined most of the northern boundary for the neighborhood. The Georgia Railroad, from Atlanta’s earliest days, has run only a few blocks north of Fair Street. Thus from the outset the city was pushing in upon Colonel Grant’s land from the north and creating barriers to residential growth such as the Fair Street artery, Oakland Cemetery, and the Georgia Railroad line.

The Atlanta city limits in 1835 were a circle with a one-mile diameter centered at the Zero Mile marker downtown. At that time the city officially included only the far northwest portion of the future neighborhood. Grant Park proper was an attractive amenity that encouraged suburban development in the surrounding area. Development in the western section of the neighborhood began in the 1880s after Grant subdivided and sold residential lots. By 1893 maps show that almost all of the present day roads were designed, if not built. In order to attract prospective home builders, developers used the availability of amenities such as public transportation or recreational areas to enhance their real estate and to make it more attractive to buyers. Grant must have known that a city recreational area would increase the value of his property in this area, and he later worked to extend the streetcar line out to Georgia Avenue to link his landholdings to the downtown area.

In 1883, the Metropolitan Street Railway Company established a streetcar service along what is now Park Avenue to a pavilion in Grant Park. Boulevard Avenue was extended southward into the Grant Park neighborhood in 1893. Street extensions and public transportation improvements resulted in rapid growth for the entire Grant Park residential area. After about 1890 Grant Park’s recreational facilities, and street rail service bringing Atlantans to the zoo, had established the area as a popular residential and recreational development. By 1902 there were street railway lines along Fair Street (Memorial Drive), Woodward Avenue to Cherokee, Hill and Grant Streets south to Augusta Avenue, Georgia Avenue east to the park, and Cherokee south to Ormond.

The parkland itself has always been open to all citizens. Grant placed no racial restrictions in the deed for the park, but the zoo and cyclorama developed later and were restricted to allow whites only. The Grant Park neighborhood was once solidly white and composed exclusively of single family houses of the middle and lower-middle classes. Today the neighborhood has a diverse population that reflects the cultural makeup of Atlanta. The lands around the park annexed by the city in 1885 were soon subdivided and sold as residential lots. As a result, much of the housing in the community was built around the turn of the century or just thereafter.

By 1883, Grant’s plans to subdivide his land must have been well advanced, for in May 17 of that year he donated to the City, the first one hundred acres of what would become known as Grant Park. In 1885, by a uniform added distance from the Zero Marker, the City extended its limits between one-half and one mile in order to include the donated Park, and in the process, virtually all other land owned by LP Grant. In 1888, a streetcar line extended into the Park and in 1884 a rudimentary zoo appeared.

In 1889, Atlanta lumber merchant George V. Gress gave the City a collection of former circus animals and buildings to house them in Grant Park. That was the beginning of what was to become the Municipal Zoo, now Zoo Atlanta. In April, 1890, the City purchased 44 acres from Grant to the north of the original tract in Land Lot 44 to bring the total acreage of the park area to 131.5 acres. In 1893, Mr. Gress donated The Cyclorama, a large circular painting of the Battle of Atlanta, painted by German artists in Milwaukee, 1885-1886, to the City and it was moved to Grant Park and housed in a circular, wood shingled building, since replaced by a substantial masonry structure.

There are several significant individuals that have been a part of the Grant Park neighborhood. Of course there is Lemuel P. Grant for whom the area is named for, who was instrumental in bringing the railroad to Atlanta, a large landholder in the area, a prominent individual in the area, and the person who donated his land for a park and recreation area. There is also former Atlanta Mayor William B. Hartsfield who resided in the Grant Park neighborhood at the time of his election to mayor in the 1930s. Hartsfield for whom the Atlanta International Airport is named strongly promoted the city as an airline hub. The City Limits of Atlanta were also greatly expanded during his administration.

Grant was made a colonel in the Confederate Army in 1862. During late 1863 and early 1864, Grant was responsible for the design and construction of a system of defensive fortifications for the City of Atlanta. A section of the main line of these earthen breastworks bbbisected some of Grant’s property that now lies within Grant Park and a southeast salient extended to the southeast corner of the park where Fort Walker is still in evidence.

After the war, Grant expanded his business career. He continued his railroad activity (becoming an officer of several lines), participated in early street railway building, developed his real estate interests and served local government in several capacities. In 1869 Grant became a member of Atlanta’s first Board of Education and was very active in the 1870s in establishing the public school system in Atlanta. At one time, Grant’s land holdings made him the largest landowner in southeast Atlanta.

As might be expected from its name, the neighborhood owes much of its development primarily to decisions made by Lemuel Pratt Grant, particularly his decisions first to buy large tracts of land southeast of the city in the 1840s and 1850s, second, to hold the tract through the 1870s, and finally to subdivide and sell them in the 1880s. A second formative force has persistently influenced the area’s development: the growth and resultant need for housing in Atlanta itself. This growth alternately circumscribed and spurred the Neighborhood’s growth through several eras, from the first streetcar lines up through the building of the superhighway. The interplay between the private decisions of Grant and landowners like him and the public need for residential sites around the blossoming downtown districts defines much of the development of the neighborhood.

Initially, the early neighborhood must have seemed a nearly rural domain on the fringes of bustling Atlanta. In the 1850s the city founded its main cemetery, Oakland, on the north side of Fair Street (Memorial Drive). Oakland Cemetery has ever since defined most of the northern boundary for the neighborhood. The Georgia Railroad, from Atlanta’s earliest days, has run only a few blocks north of Fair Street. Thus from the outset the city was pushing in upon Colonel Grant’s land from the north and creating barriers to residential growth such as the Fair Street artery, Oakland Cemetery, and the Georgia Railroad line.

The Atlanta city limits in 1835 were a circle with a one-mile diameter centered at the Zero Mile marker downtown. At that time the city officially included only the far northwest portion of the future neighborhood. Grant Park proper was an attractive amenity that encouraged suburban development in the surrounding area. Development in the western section of the neighborhood began in the 1880s after Grant subdivided and sold residential lots. By 1893 maps show that almost all of the present day roads were designed, if not built. In order to attract prospective home builders, developers used the availability of amenities such as public transportation or recreational areas to enhance their real estate and to make it more attractive to buyers. Grant must have known that a city recreational area would increase the value of his property in this area, and he later worked to extend the streetcar line out to Georgia Avenue to link his landholdings to the downtown area.

In 1883, the Metropolitan Street Railway Company established a streetcar service along what is now Park Avenue to a pavilion in Grant Park. Boulevard Avenue was extended southward into the Grant Park neighborhood in 1893. Street extensions and public transportation improvements resulted in rapid growth for the entire Grant Park residential area. After about 1890 Grant Park’s recreational facilities, and street rail service bringing Atlantans to the zoo, had established the area as a popular residential and recreational development. By 1902 there were street railway lines along Fair Street (Memorial Drive), Woodward Avenue to Cherokee, Hill and Grant Streets south to Augusta Avenue, Georgia Avenue east to the park, and Cherokee south to Ormond.

The parkland itself has always been open to all citizens. Grant placed no racial restrictions in the deed for the park, but the zoo and cyclorama developed later and were restricted to allow whites only. The Grant Park neighborhood was once solidly white and composed exclusively of single family houses of the middle and lower-middle classes. Today the neighborhood has a diverse population that reflects the cultural makeup of Atlanta. The lands around the park annexed by the city in 1885 were soon subdivided and sold as residential lots. As a result, much of the housing in the community was built around the turn of the century or just thereafter.

By 1883, Grant’s plans to subdivide his land must have been well advanced, for in May 17 of that year he donated to the City, the first one hundred acres of what would become known as Grant Park. In 1885, by a uniform added distance from the Zero Marker, the City extended its limits between one-half and one mile in order to include the donated Park, and in the process, virtually all other land owned by LP Grant. In 1888, a streetcar line extended into the Park and in 1884 a rudimentary zoo appeared.

In 1889, Atlanta lumber merchant George V. Gress gave the City a collection of former circus animals and buildings to house them in Grant Park. That was the beginning of what was to become the Municipal Zoo, now Zoo Atlanta. In April, 1890, the City purchased 44 acres from Grant to the north of the original tract in Land Lot 44 to bring the total acreage of the park area to 131.5 acres. In 1893, Mr. Gress donated The Cyclorama, a large circular painting of the Battle of Atlanta, painted by German artists in Milwaukee, 1885-1886, to the City and it was moved to Grant Park and housed in a circular, wood shingled building, since replaced by a substantial masonry structure.

There are several significant individuals that have been a part of the Grant Park neighborhood. Of course there is Lemuel P. Grant for whom the area is named for, who was instrumental in bringing the railroad to Atlanta, a large landholder in the area, a prominent individual in the area, and the person who donated his land for a park and recreation area. There is also former Atlanta Mayor William B. Hartsfield who resided in the Grant Park neighborhood at the time of his election to mayor in the 1930s. Hartsfield for whom the Atlanta International Airport is named strongly promoted the city as an airline hub. The City Limits of Atlanta were also greatly expanded during his administration.

Architectural Significance

Grant Park has a significant collection of historic houses reflecting various styles of late Victorian and early 20th century residential housing trends. Queen Anne and Folk Victorian styles are found dating from Grant Park’s earliest period of development in the 1870s and 1880s. These were followed later by the Craftsman bungalow, English Vernacular Revival as well as a few Shotgun and Double Shotgun homes.

The Queen Anne styled houses found in Grant Park are primarily homes with design elements that include steep pitched irregular roof lines, asymmetrical massing, turned front porch supports with decorative spindlework, and an occasional turret. Leaded glass in the windows and differently textured wooden shingles are also common in these relatively modest homes and can be seen throughout the Grant Park neighborhood. Homes built in the Queen Anne style were Georgia’s most popular residential homes in the 19th century. There are many excellent examples of the Queen Anne style home in Grant Park.

The Folk Victorian homes in Grant Park are mostly one-story cottages and consist of a house type that is either a gabled ell or has a central hallway. The decorative features added to the simple folk house type define the style. Ornamental features in the form of bric-a-brac, or gingerbread are added to the porch, gables, and around the door and window casings.

There are several clusters of homes constructed in the English Vernacular Revival style scattered throughout Grant Park. Although there are not many examples of the English Vernacular Revival style in the neighborhood, it was a common style constructed throughout the country from the early part of the twentieth century. The defining architectural characteristics include steeply pitched roofs, brick exteriors often interspersed with stone, decorative half-timbering, arched front entries, and asymmetrical front facades. The English Vernacular Revival resources constructed in Grant Park are fairly modest examples of the style, which is in keeping with the overall middle class setting of the neighborhood.

In the early 20th century, the prevalent residential style is the Craftsman bungalow. The Grant Park neighborhood has many examples of this early style. The distinctive elements of this style include a low pitched roof that is either front gabled or hipped thus giving a generally horizontal effect, deep overhangs with exposed rafter ends, brackets, broad front gables, porches that have short square columns set on heavy masonry piers extending to the ground. Windows may have a multi-paned sash over a large one-pane sash.

A folk style house known as the Shotgun and Double Shotgun was a popular house type in the south. There are a few examples found scattered around the north western and western side of the neighborhood. The houses are narrow gable-front dwellings one-room wide and three or more rooms long. The Shotgun houses in Grant Park are of a very simple design and little ornamentation.

The community had two Italianate mansions, one of which is left standing. They were built in 1858 and 1871 and served as family homes for Lemuel P. Grant. The 1858 house was located at 327 St. Paul Avenue and has been damaged by fire and deterioration. Historic photographs show that the house was rectangular with giant order pilasters at each corner. The roof was hipped with dormers and there was a heavy cornice supported by paired brackets. The second Grant house, built in 1871, is of stuccoed brick and frame and sits on the southwest corner of Hill and Sydney Streets. It is a prominent visual feature of the district and has Italianate wooden detailing in the eve brackets, porch posts with segmental arches, and a round arch above the front door.

The neighborhood has several churches scattered throughout the residential area. While many are small twentieth century structures, some are architecturally notable. For example, the former Georgia Avenue Presbyterian Church, on the northwest corner of Grant Street and Georgia Avenue, is an early twentieth century red-brick Gothic Revival building with pointed arch stained glass windows, a crisply detailed crenellated corner turret, and a projecting Gothic arched entrance porch. This structure is now home to the congregations of the Georgia Avenue Church and the Southwest Christian Fellowship. Diagonally across Georgia Avenue on the southeast corner of Grant Street the monumental classical portico of the buff-brick Mt. Olive Baptist Church (formerly Georgia Avenue Baptist Church) (1921) provides an interesting visual contrast. Further north on Grant Street is an 1899 church structure, the Neo-Romanesque, granite building that houses St. Paul United Methodist Church.

There are three or four business nodes and about a dozen small individual structures within the Grant Park neighborhood. Most of the older buildings are from the early to mid 1900s. They are excellent examples of early neighborhood commercial structures, many are still being used for small independent businesses.

SOURCE: City of Atlanta Urban Design Commission